Renaissance

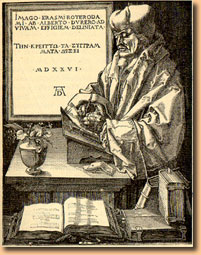

(c. 1469-1536)

Hollandske teolog som påvirket Martin Luther

Early Renaissance

Adapted and compressed from 'A History of Europe' by Norman Davies, (Oxford) Chap VII

The Renaissance is incomprehensible without reference to the depths of disrepute into which the medieval church, the previous fount of all authority, had fallen.

In that process the Christian religion was not abandoned, but the power of the church was gradually corralled within the religious sphere: the influence of religion increasingly limited to the realm og private conscience. As a result the speculations of theologians, scientists and philosophers, the work of artists and writers, and the policies of princes were freed from the control of a church with monopoly powers and totalitarian pretensions.

The great Renaissance figures were filled with self-confidence. They felt that God-given ingenuity, could and should be used to unravel the secrets of God's universe; and that, by extension, man's fate on earth could be controlled and improved. Here was the decisive break with the mentality of the Middle Ages, whose religiosity and mysticism were reinforced by exactly the oppsite conviction — that men and women were the helpless pawns of Providence.

Renaissance attitudes, in contrast, were bred by a sense of liberation and refreshment, deriving from the growing awareness of human potential. Speculation, initiative, experiment and exploration could surely be rewarded with success. Intellectual, literary and political historians analyse the beginnings from their own peculiar angle. Art historians look back to the painters Giotto and Masacio (1401-1428), to the architect Filippo Brunellesci (1379-1446), who measured the dome of the Pantheon in Rome in order to build a still more daring dome for the cathedral in Florence. Or to the sculptors Ghiberti (1378-1455) and Donatello (c.1386-1466). Every one of these pioneers was a Florentine.

After the 1453 sack of Constantinople by the Turks, Christian refugees were welcomed into Florence bringing their libraries, including ancient copies of the Greek Septuagint, with them; this encouraged the revival of “New Learning” throughout western Europe and made possible Erasmus’s later work on the Greek New Testament.

As the first home of the Renaissance, Florence can fairly lay claim to be the 'mother of modern Europe'. In those unmatched generations of versatile Florentines, no one ever outshone Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519).

The causes of the Renaissance were as deep as they were broad. But the source of spiritual developments must be sought above all in the spiritual sphere. It is no accident that the roots of Renaissance and Reformation alike are found in the realm of ideas. The new learning of the fifteenth century possessed three novel features, the third of which was the rise of Biblical scholarship based on the critical study of the original Hebrew and Greek texts. This provided an important bond between the secular Renaissance. and the religious Reformation which was to place a special emphasis on the authority of the Scriptures.

Erasmus

Enthusiastic humanist sprang up at all points from Oxford to Cracow, and their patrons, from Cardinal Beaufort to Cardinal Oleśnick, were often prominent churchmen. All paid homage to the greatest of their number, Erasmus of Rotterdam.

Gerhard Gerhards (c.1466-1536), a Dutchman from Rotterdam, better known by his Latin and Greek pen-names of 'Desiderius' and 'Ersamus', was a frequent visitor to London and Cambridge, and long-term resident of Basle. Erasmus made himself the centre of the scientific study of Divinity.

Like his close friend Thomas More, he was no less a Pauline than a Platonist. His publication of the Greek New Testament (1516) was a landmark event. Its preface contained the famous words: I wish that every woman might read the Gospel and the Epistles of St. Paul. Would that these were translated into every language... and understood not only by Scots and Irishmen but by Turks and Saracens. Would that the farmer might sing snatches of Scripture at his plough, that the weaver might hum phrases of Scripture to the tune of his shuttle...

He was a true protestant against the church's abuses, but took no part in the Reformation: a devoted humanist and a devoted Christian. His books remained on the Church's Index for centuries but were printed freely in England, Switzerland and the Netherlands.

Erasmus greatly influenced the language of the age. His collection of annotated Adagia (1508) was the world's first bestseller, bringing over 3000 classical proverbs and phrases into popular usage:

- oil on the fire

- flog a dead horse

- milk a billy-goat

Historians like to portray the Renaissance as a bipolar battle between the traditional narrow-minded Christian Church and enlightened humanists who saw the error of the church's ways. These latter innocently pursued their consciences while being persecuted by religious bigots.

Notwithstanding its intentions, traditionalists belived that The Renaissance was the destruction of religion and ought to have been restrained. 500 years later, with the disintegration of Christendom far more advanced, it has been proved to be the source of all the rot. As one Catholic philosopher says: The Renaissance was not the Middle Ages plus Man, but the Middle Ages minus God. A Russian Orthodox commentator: Unfortunately the Renaissance also began to assert man's self sufficiency... God became the enemy of Man and Man of God.

Dependance on God and conscience can easily be mistaken for self-sufficiency by an organisation that presumes to have a monopoly on spritual matters.

In fact both in its fondness for pagan antiquity and in its insistence on the exercise of man's critical faculties, Renaissance humanism did indeed contradict the prevailing modes and assumptions of Christian practice, but not neccessarily Christian revelation. This third way belonged to many of the Renaissance masters, few of whom saw any contradiction between their 'humanism' and their religion, and most modern Christians would agree. Some developments deriving from the Renaissance, from Cartesian rationalism to Darwinian pseudo-science, have been judged by fundamentalists to be contrary to revelation, yet Christianity, defined as organised Church religion, has adapted and accomodated them. But despite the growing prominence of secular subjects, the overwhelming bulk og European art, for instance, continued to be devoted to religious themes; and all the great masters were great believers.

These great innovative figures include Paolo Uccello ( 1397-1475), conqueror of pespective, Andrea Mantegna (1431-1506), master of realistic action, and Sandro Botticelli (1446-1510), the magical blender of landscape and human form and the three supreme giants Leonardo da Vinci, Raphael Santi and the mighty Michelangelo. Moreover the possession of a popular literary tradition in the vernacular was to become one of the key attributes of modern national identity. This tradition was established in English by the Elizabethan poets and dramatists Spenser, Marlowe and Shakespeare, whose plays expound many gospel truths.

Clearly the Renaissance had something in common with the older movement for church reform. Humanists and would-be reformers both fretted against fossilized clerical attitudes and by encouraging the critical study of the New Testament, they both led the rising generation to dream about the lost virtues of primitive Christianity.

Gutenberg

The printing press of Johann Gensfleisch zum Gutenberg started work c. 1450 in the Rhineland city of Mainz. It possessed the inestimable facility for the text of a book to be set up, edited, and corrected before being reproduced in thousands of identical copies. Gutenberg is probably best remembered for his 43-line and 36-line Bibles, but he also printed an encyclopedia compiled by the 13th cent. Genoese Giovanni Balbo. This printed 'Book of Universal Knowledge' marked the first item of secular litterature in mass circulation and is prefaced with, 'With the help of the Most High...this noble book has been printed...in the Year of the Lord's incarnation 1460, in the noble city of Mainz.'

The power of the printed word inevitably aroused the fears of the religious authorities, hence Mainz, the cradle of the press, also became the cradle of censorship.

Europe's earliest censorship office was set up jointly by the electorate of Mainz and the city of Frankfurt. The first edict issued by the Frankfurt censor against printed books banned vernacular translations of the Bible.

In contrast to Christendom, the Islamic world exercised a total ban on printing until the 19th cent. The consequences, for Islam, for the spread of knowledge in general and for the political repercussions of the early 21st cent, can hardly be exaggerated.

State

State formation has been analysed in many ways. Three types of state have prevailed, tribute-raising empires, systems of fragmented sovereignty, and national states. Their internal life-force has been dominated either by the concentration of capital, as in Venice or the United Provinces, or by the concentration of coercion, as in Russia, or by varying concentrations of the two as in Britain, France or Prussia. Nation building through money and violence being the prime movers of the 100 major wars in Europe since the Renaissance.